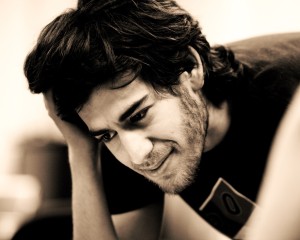

A little over a year ago, a 26-year-old programmer and activist was murdered. His name was Aaron Swartz, and although he was found hanged in his Brooklyn apartment, and his death ruled a suicide, there is little question whose hands are stained with his blood. He was pursued mercilessly by a bullying prosecutor with a long track record of ruining the lives of brilliant (and perhaps naive) young men who didn’t play by the state’s rules. And he was betrayed by an educational institution that once prided itself on not playing by the rules, either.

Those are some of the heartbreaking and infuriating insights from a story in this month’s edition of Boston magazine about Aaron Swartz’ arrest and indictment, his father Bob’s attempts to extricate his son from the legal mess, and the relentless pressure by federal prosecutors to make an example of him. The punishment they sought for Aaron was draconian even by the feds’ standards: 13 felony counts under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), with a possible prison term of 35 years, and a $1 million fine. Bank robbers and terrorists have received more lenient sentences. But U. S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz declared that Swartz’ prosecution would serve as a warning to other “hackers” about “stealing” from computers.

What did Swartz “steal”, exactly? Nothing. He downloaded files from JSTOR, an online archive for academic journals. Swartz used the network at MIT, where his father served as an adviser, under its “open access” policy, which included its subscription to JSTOR. Swartz had long held the view that scientific research should be freely available and not locked away behind a paywall. This wasn’t even the first time Swartz had performed such a download; in 2008 he grabbed 2.7 million documents from PACER, a federal court document system that usually charged for such access, even though they were public records. That attracted the FBI’s attention, but they found Swartz had committed no crime.

What did Swartz “steal”, exactly? Nothing. He downloaded files from JSTOR, an online archive for academic journals. Swartz used the network at MIT, where his father served as an adviser, under its “open access” policy, which included its subscription to JSTOR. Swartz had long held the view that scientific research should be freely available and not locked away behind a paywall. This wasn’t even the first time Swartz had performed such a download; in 2008 he grabbed 2.7 million documents from PACER, a federal court document system that usually charged for such access, even though they were public records. That attracted the FBI’s attention, but they found Swartz had committed no crime.

Swartz in fact had devoted much of his young life to finding ways to liberate information. Some of his earliest work included coauthoring the RSS 1.0 specification, a syndication format for Web-based content; founding a company to create wiki-based technology, which eventually merged with Reddit; and co-founding Demand Progress, an online advocacy group known mainly for its opposition to the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA). Swartz had also worked with Lawrence Lessig, a law professor and an advocate for intellectual property reform, studying under him at Stanford and later as a research fellow at Harvard. Swartz aided Lessig in developing the Creative Commons alternative copyright framework.

Given Swartz’ professional credentials and his history of “hacktivism”, what made his bulk downloads from JSTOR any more egregious than his previous exploits? The fact that Secret Service agents responded to the report of a “security breach” in the MIT network provides a possible clue:

When the Secret Service arrived, Bob [Swartz] says, the first thing they asked was whether any of the university’s classified research was threatened.

It wasn’t, but the nature of Swartz’ download, from a laptop hidden in a utility closet, made it look more suspicious to the feds. And it’s not surprising that a university receiving nearly a billion dollars in federal grants might toe the line with regards to any demand from the government, its hacker ethic be damned.

Intellectual property enforcement also played a role in Swartz’ prosecution. JSTOR subscriptions are not cheap, costing schools up to $50,000 per year. But MIT had a policy that not only allowed anyone on campus to use their network, but did not require authentication to access JSTOR. It was only after Swartz’ bulk download that suddenly “unauthorized network access” became an issue, allowing him to be charged under the CFAA. At worst, Swartz cost JSTOR some bandwidth during his download (to its credit, JSTOR settled with Swartz out of court and pursued no further legal action), but he didn’t steal anything. The concept of intellectual property, and the framework used by the state to enforce copyright, rests on the logically bankrupt notion that downloading a copy of something without permission constitutes “theft”. Never mind that Swartz did have permission in this case — once he broke some imaginary and unwritten rule (“too many documents”, apparently), his action rose to the level of a felony in the federal government’s view. This preposterous reasoning was all prosecutors needed to go after Swartz.

It was Aaron’s misfortune that he did his deed in a district with one of the country’s most notorious cyber-crime prosecutors. Stephen Heymann, the lead prosecutor in Swartz’ case, is no stranger to ruining young men’s lives. In 1994 Heymann prosecuted a student, also at MIT, for creating a bulletin board system which allowed users to trade copyrighted software (a precursor to the file-sharing networks common today). His case was dismissed on grounds that he didn’t intend to profit from the downloads, which prompted Congress to strengthen the CFAA to allow prosecution even if profit wasn’t a motive.

Heymann later won the conviction of 16-year-old Jonathan James, who had gained access to NASA and Department of Defense systems, and became the first juvenile to be incarcerated (via house arrest) for hacking. Heymann again targeted James in 2008, in an investigation of an identity theft ring tied to break-ins of department store networks. Although the Secret Service never found any evidence James was involved in the hacks, he killed himself in 2008, saying he had “no faith in the ‘justice’ system.”

Nor should anyone else, really. The system has never been about “justice,” and it seemed even less so in the circumstances surrounding Aaron Swartz’ case. This case was about projecting government power and crushing anyone who dared to upset the status quo, as Swartz often did. And anyone wishing to remain in the elites’ good graces — like MIT, and most other public research universities — had best do whatever is necessary to please their masters. And despite their pleas of “neutrality” in this case, MIT administrators did exactly that. They provided Heymann with every scrap of information they had about Swartz’ activities, usually with just a phone call. Bob Swartz pleaded with them to negotiate a settlement, asking: “Why are you destroying my son?” The school never gave him a satisfactory answer.

With the arrogance characteristic of state prosecutors, Heymann seemed shocked at Swartz’ temerity to fight the charges. Most outrageously, he likened Swartz to a rapist:

Negotiations continued, but in the end Aaron told Heymann no. He would fight the felony charges and go to trial.

Later, Heymann would tell MIT that he was “dumbfounded” by Aaron’s decision, and claimed that Aaron was “systematically re-victimizing” the university by choosing to go through proceedings. Publicly criticizing MIT at a trial, Heymann said, was akin to “attacking a rape victim based on sleeping with other men.”

If anyone was “raped” in this scenario, it was Aaron. Humiliated, cut off from many of his friends — his relationship with his girlfriend, Quinn Norton, ended after Norton tried to talk to Heymann and wound up giving the prosecutor a key piece of evidence against him — and seeing no end to the persecution, Aaron Swartz decided to end it himself.

In the end, there were no winners. No one was ever hurt by Swartz’ actions, no vital national interest served, no copyrights protected, no damage to repair. Instead the world lost a brilliant young mind who understood better than most the power knowledge has to liberate the world. Perhaps the state understands that too, which is why it tries so desperately to crush those who attempt to set it free.